The Form-Based Code Template is a tool to help facilitate the establishment of a form-based code ordinance. Form-based code is an emerging ordinance type that, unlike traditional zoning, emphasizes physical form to regulate and guide development and implement the vision for a place.

The Form-Based Code Template is a tool to help facilitate the establishment of a form-based code ordinance. Form-based code is an emerging ordinance type that, unlike traditional zoning, emphasizes physical form to regulate and guide development and implement the vision for a place.

Form-based codes specify design for places and centers through a comprehensive process that relies on local decision making, and allows for uses to adapt based on demand. Form-based code sets a design standard rather than a minimum requirement and encourages active, vibrant communities that are both highly functional and aesthetically pleasing.

This tool is a template to guide the creation of form-based code. It is ready for calibration to any community. The template was designed with the intention to simplify the creation and implementation of a form-based code.

The tool is free to access. There are two possible methods to use this tool, including the digitally interactive use of Adobe InDesign or calibration through Adobe Acrobat portable document format (PDF). Internet access is required to use either of these methods.

For additional information regarding the tool, please contact Ted Knowlton.

Form-based codes can benefit a community in a wide variety of ways, from increased economic value to easier development approvals. While the code consists of a series of separate components, they are meant to be used together to achieve the highest level of benefit.

Form-based codes can benefit a community in a wide variety of ways, from increased economic value to easier development approvals. While the code consists of a series of separate components, they are meant to be used together to achieve the highest level of benefit.

Focus on the Public Realm

Form-based codes focus on the way in which buildings interact with the street. They create pedestrian friendly environments by controlling physical elements of buildings such as setbacks and minimum transparency levels. They also use street type requirements that work cooperatively with building type regulations to create an attractive, pedestrian-friendly environment. These regulations often include specifications for sidewalks, travel and bicycles lanes, and street trees.

Predictable Results

Form-based codes define the form and general appearance of buildings as primary concerns and consider land use as a secondary concern. The benefit of placing building form over building use is that the community can control the physical impact development has on a community. This allows for a greater mix of uses, which encourages a more diverse and walkable community. It also makes the development process more streamlined and predictable. Clearly communicating the design, density, and use elements up front in the process with a form-based code, results in fewer contentious hearings (after adoption) since all parties know what is expected from the beginning.

Codified Requirements

Form-based codes differ from design guidelines in two major ways. Form-based codes codify the design elements they specify, where design guidelines in many communities are merely encouraged. Also, form-based codes do not generally specify architectural styles, ornamentation, or elements like colors that are typically suggestions found in design guidelines. This ensures a variety and flexibility of designs and building elements within the district. The manual/template treats many of these stylistic design features as an optional chapter.

Place-Specific Regulations

Form-based regulations are tailored and calibrated for their communities, where conventional codes rely heavily on suburban development that is often generic in nature and do not take the character of the preexisting community into account. Since form-based codes take the surrounding neighborhood context into consideration when assigning street and building types, the existing community characteristics are preserved and encouraged. If a community is engaged in a form-based code in an area where no particular form is considered worth reinforcing, the form-based code can achieve, through community input, a new, more desirable form. They also make the transit and land use connection a standard, where traditional zoning can make it an afterthought.

Built from Community Preference

Form-based codes embrace the public design process. Specific input from key stakeholders, community leaders, and city officials through interactive processes as community charrettes or image preference surveys (a process used to facilitate public discussion and to document how citizens want their community to look) provide a true representation of a community’s interests.

Highly Illustrated Document

A defining feature of form-based codes is their easy-to-use, illustrative nature both graphically and carefully crafted, straightforward narrative. They streamline repetitive information and provisions, placing everything together in one ordinance, resulting in a more concise code document.

Levels of Control

Not all form-based codes are the same and they give communities flexibility with how prescriptive the regulations are and how they are applied. Some communities choose a fundamental approach where only building envelope regulations are regulated in an overlay zone. Other communities want stricter standards and choose to regulate elements like facade treatments or building materials in entirely new districts. This customizable approach ensures that the amount of regulation is appropriate for each community. It is not anticipated that all the components of the manual/template will be used in the final ordinance, but that the process will debate all of them.

Economic Benefits

Form-based codes promote the development of walkable neighborhoods, which brings economic benefits like higher real estate values and increased occupancy rates. Homes in walkable neighborhoods have experienced less than half the average decline in price from the housing peak in the mid-2000s (Brookings Institution, 2011). In addition, the emphasis on permitted uses instead of conditional uses, decreases the amount of time and risk for developers.

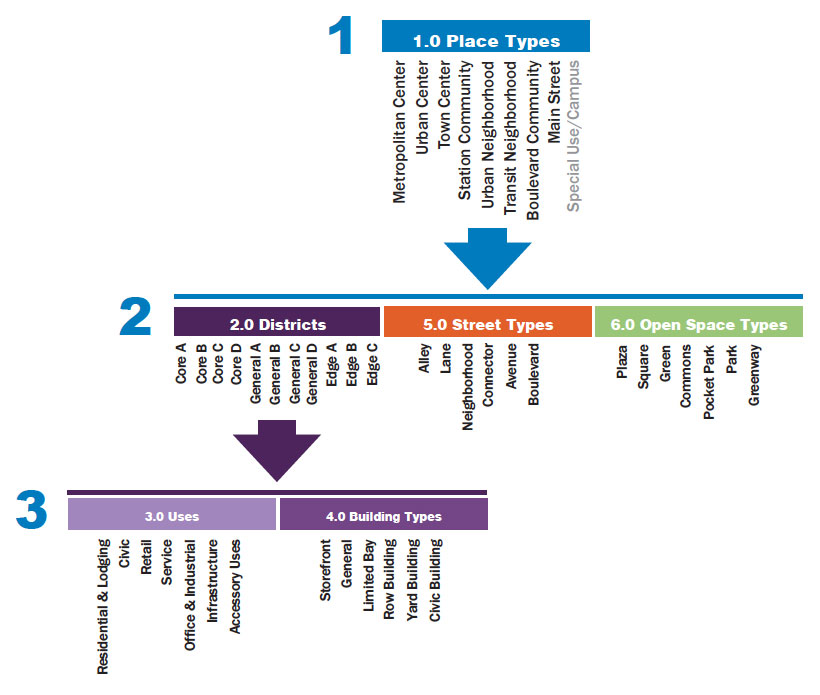

The template form-based code is made up of six primary sections designed interact with each other, including place types, districts, uses, building types, street types, and open space types. All information should be calibrated specifically to meet the goals and vision of a specific place.

The template form-based code is made up of six primary sections designed interact with each other, including place types, districts, uses, building types, street types, and open space types. All information should be calibrated specifically to meet the goals and vision of a specific place.

Tier 1: Place Types

The place types make up the organizing structure for the template code. Application of the code to a particular location requires selecting and calibrating one of the provided place types to either represent the existing, desired, or a combination, and use of the place. Each place type then permits a unique combination of the other elements, ultimately working together to result in the desired physical form for the area.

Note that a special use/campus place type is not included in the template code, as the requirements for this (likely) single use place would be very specific to that single use. The districts (uses and building types) would not be applicable to such a place, but are geared more toward walkable centers and corridors with a mix of uses.

Tier 2: Districts, Streets, and Open Space

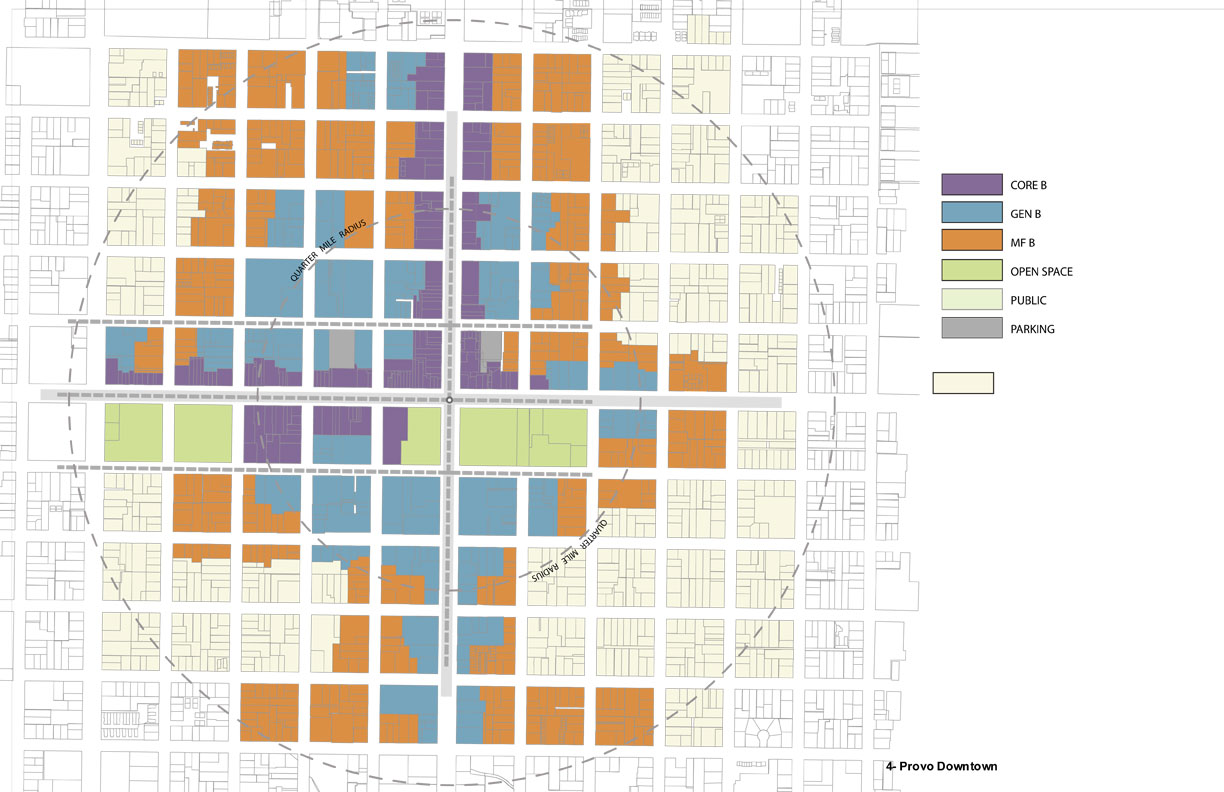

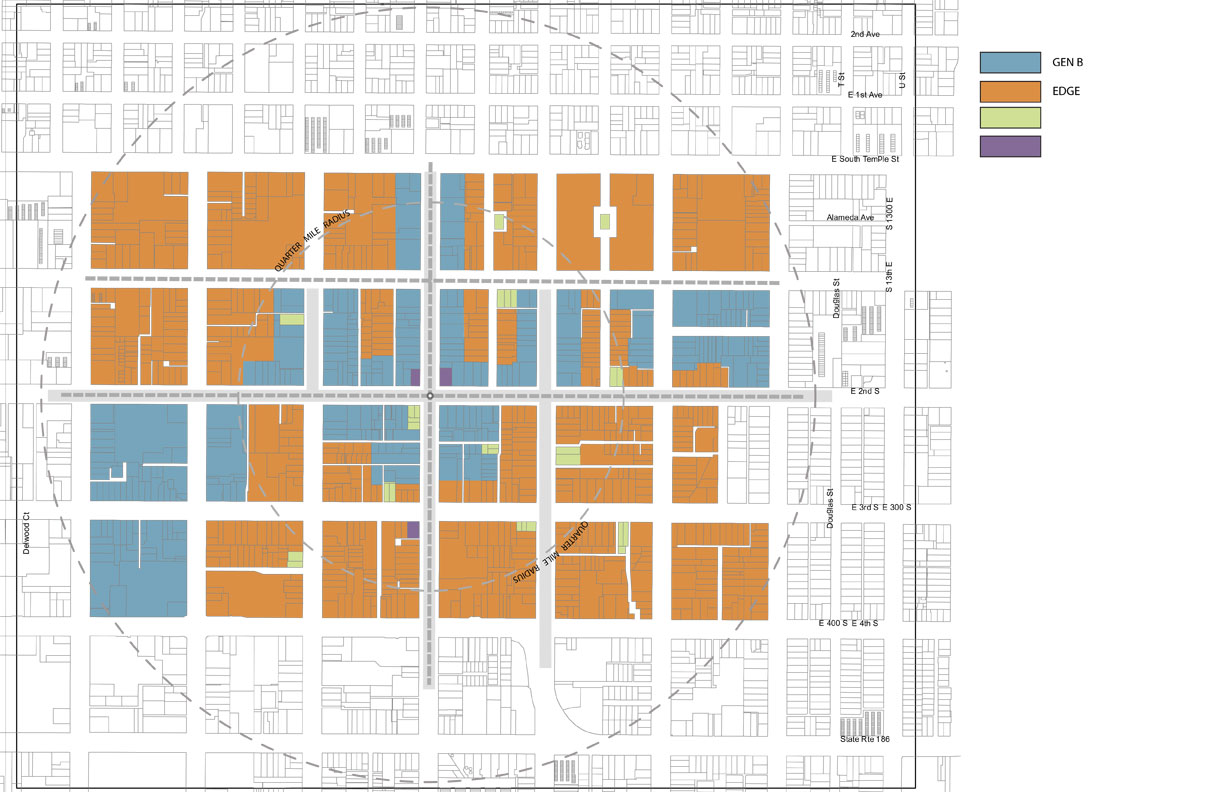

Each place type permits a unique mix of districts, street types, and open space types. Different quantities of the districts also help define the place types. For example, the metropolitan center consists mainly of core and general districts; while the urban neighborhood consists mainly of general and edge districts. The combination of districts, streets, and open space work together to create an identifiable public realm, defined by the streetscape from the building face to building face on opposite sides of the street.

Tier 3: Uses and Building Types

Districts permit a mix of uses and building types. Some districts permit a fairly succinct set of uses permitted within only a couple of building types, while other districts are very flexible, permitting a wide range of uses in a variety of different allowed building types.

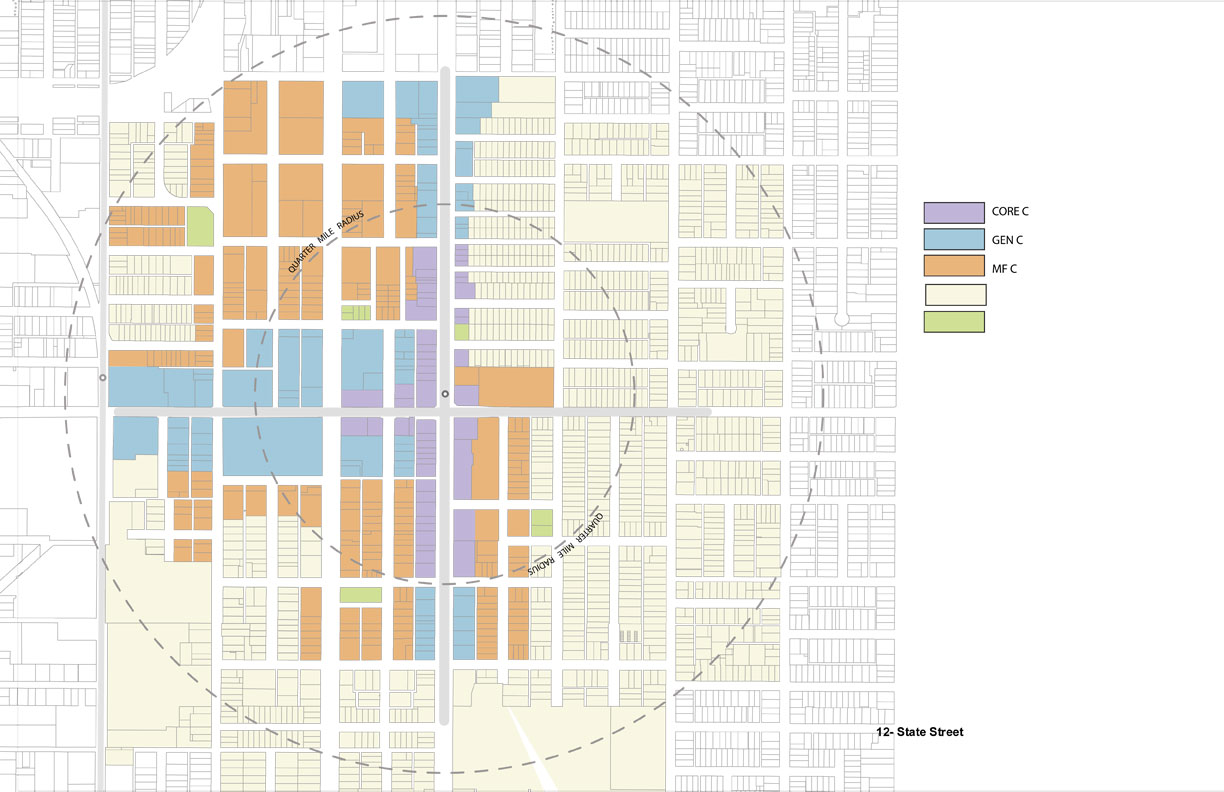

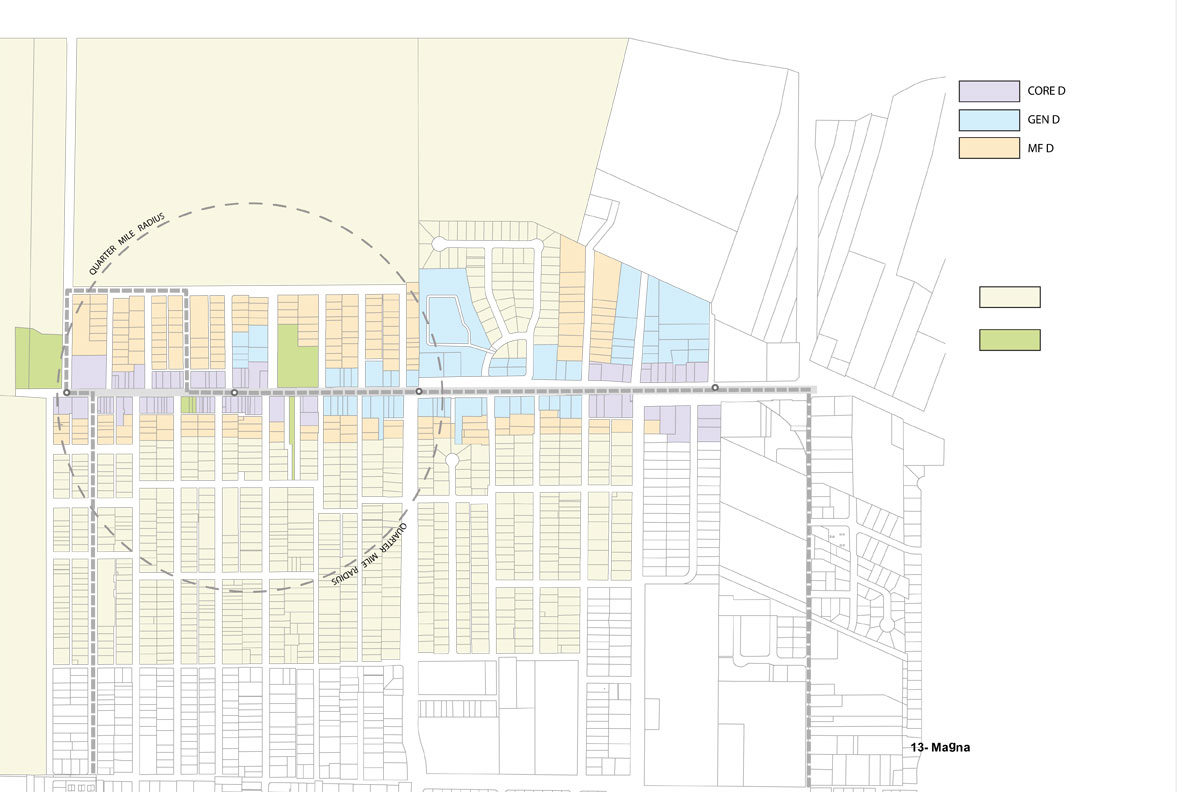

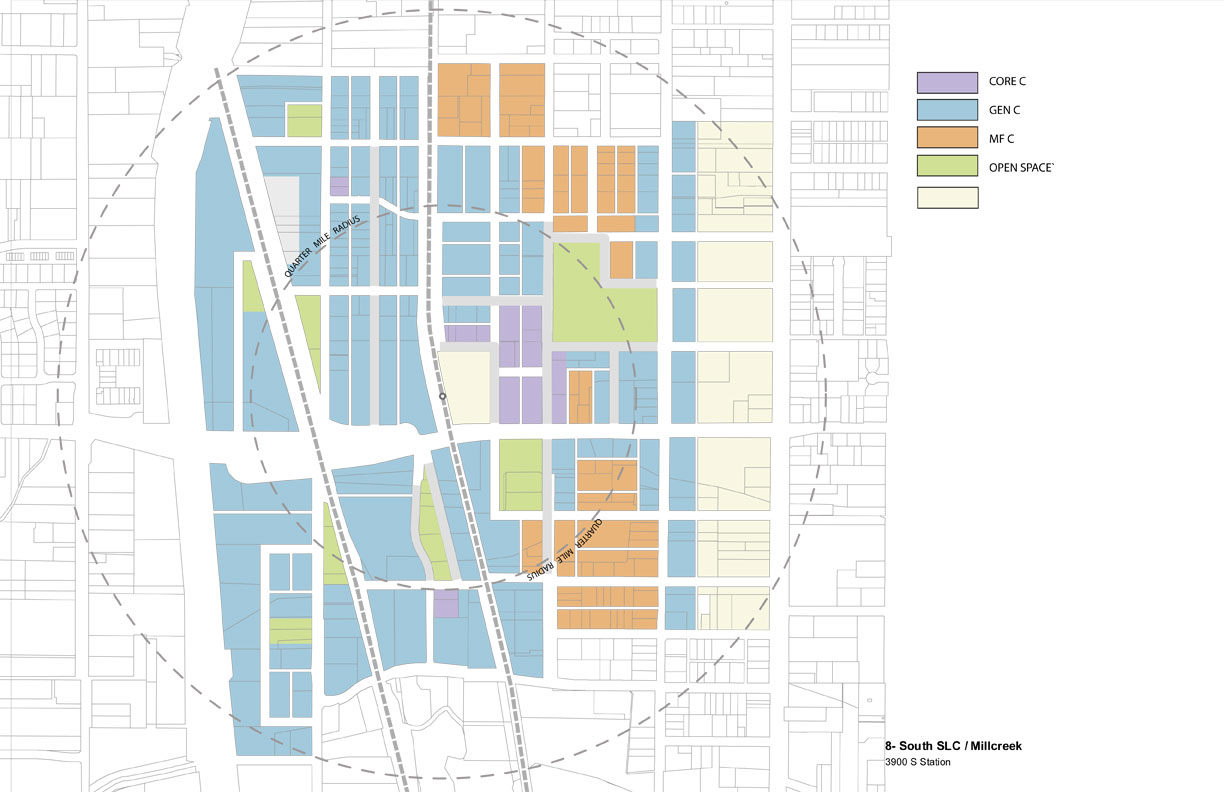

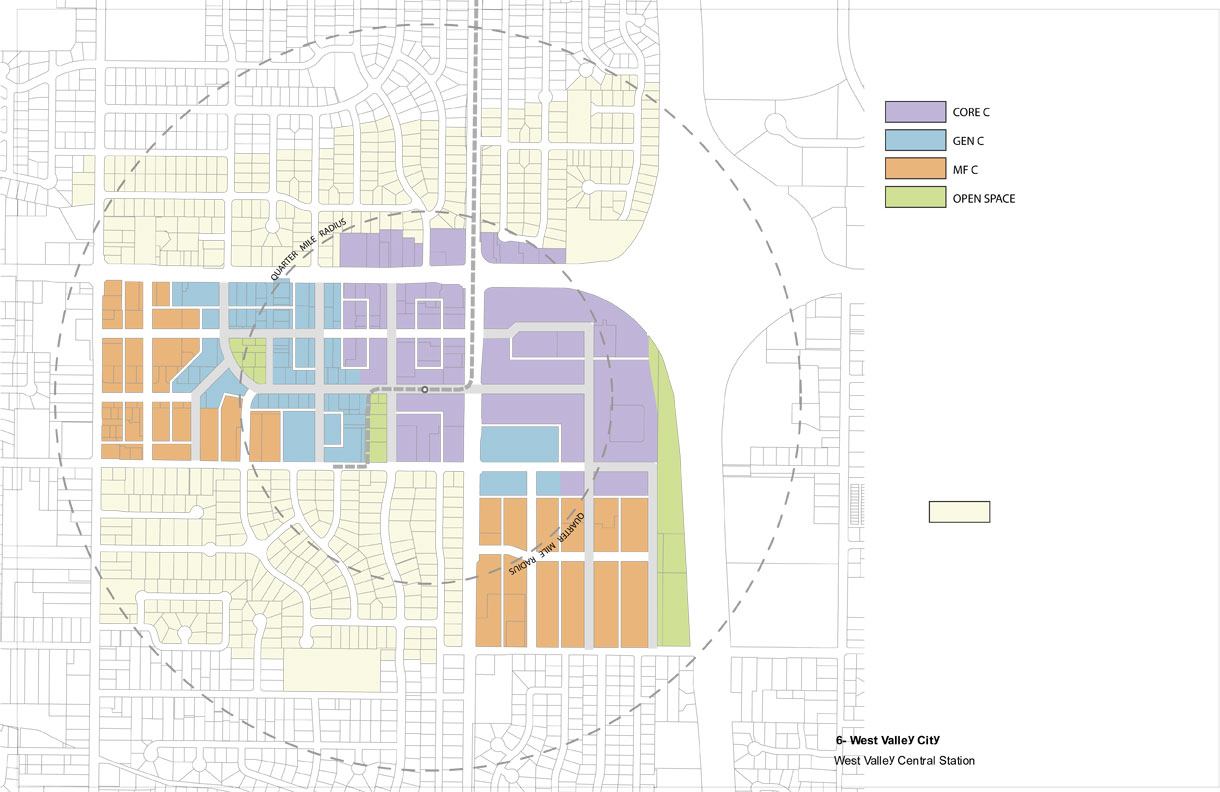

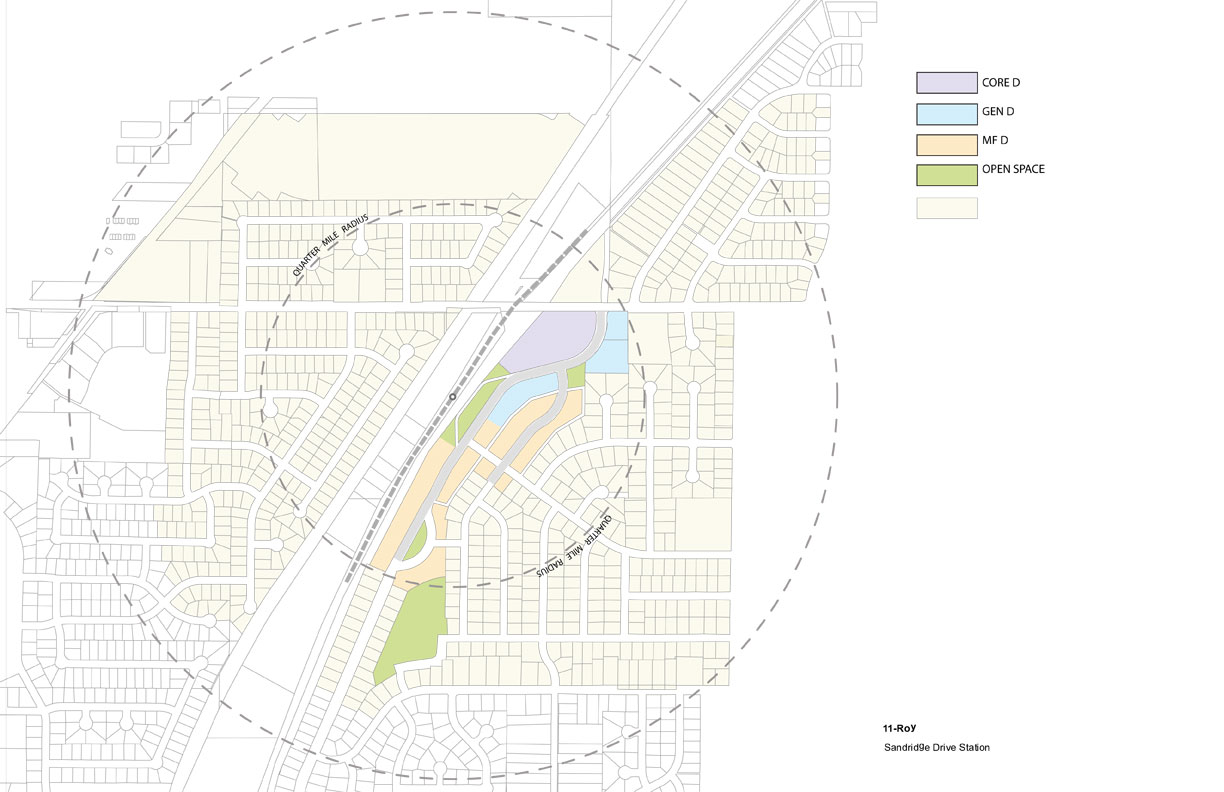

Eight place types were developed for the Wasatch region based on characteristics including station context, land use, development pattern, and scale. The place types form the basis of the template code.

Using the Template Code Place Types

Each center or corridor can be categorized into a place type that is based on station context. Characteristics such as land use, development pattern and intensity, scale, and type of transit all are considered when applying a place type. The place types are meant to guide the user to the appropriate form-based recommendations specifically developed for each kind of station context.

Choosing a Place Type

The place types serve as a framework for zoning districts, street and block definition, and open space. Identify the appropriate place type closest to the desired future for the place.

Centers, Neighborhoods, and Corridors

The place types are organized into three categories: centers, neighborhood, and corridors.

Centers are those areas defined in the Wasatch Choice process as centers of activity, on the regional, community, or neighborhood scale. Utilizing the Wasatch Choice plan, the metropolitan center, urban center, and town center place types were identified.

The neighborhood place types consist mainly of residential with support retail and service uses. The station community, urban neighborhood, and transit neighborhood were defined to fulfill a variety of scales of mainly residentially focused place types, with the station community also providing the potential for employment uses.

The corridor place types are more linear in nature than the centers or neighborhoods, and include the boulevard community and main street.

Components of Complete Places

The template code place types were developed to be complete places. When implemented, residents and visitors of these places will have access to basic goods and services that meet their daily needs, as well as a variety of housing types, open space, and transportation choices. The following components are reflected in the template code

Mix of Land Uses

By providing a mix of uses, opportunities for retail, services, and offices can develop close to residential areas. Residents have the opportunity to live close to where they work and shop. This proximity means that residents are more likely to walk, take transit, or bike to their destinations.

Mix of Housing Types

In addition to a mix of uses, a mix of housing types is important to a complete neighborhood. A “lifecycle of housing” refers to the idea that residents can choose to age in place without leaving their neighborhood. A mix of townhomes, apartments, and single-family homes at varying densities are available for students, young professionals, families, and senior citizens. The template code promotes this idea by allowing multiple building types in all districts and provides guidelines on how district relationships interact with each other.

Transit Service

Transit service is an integral part of a complete neighborhood. Transit-oriented development is the concentration of residential, commercial, and office uses within a quarter to a half mile of a transit station. Within this radius (equivalent to about a ten-minute walk) people are more likely to use the transit system and walk to destinations from the station. Close station spacing, like service with streetcars or trolleys, creates a more contiguous development, whereas commuter train service yields more nodal centers that step down radially. At the core of the development, commercial and residential density is higher and lowers further out of the center. The template code will encourage these kinds of densities within its districts.

Active Transportation Priorities

Designing streets for all users, not just cars, is known as designing for complete streets. Physically designing streets and infrastructure for active transportation makes residents and visitors more likely to participate, as well as feel safer when walking or biking. Streets should be designed to include both vehicular and comfortable pedestrian realms within the area’s existing and proposed transportation system. Basic elements for pedestrian and biking infrastructure such as sidewalks, street trees, and on-street parking to buffer pedestrians, crosswalks, and marked bicycle lanes or share lanes should be included in all locations.

Access to Open Space and Recreation Opportunities

It is important for neighborhood residents to have access to parks and other types of outdoor recreation. Residential units should be no more than a three-and-a-half-minute walk from an open space or park. This access provides people of all ages with recreation and exercise opportunities, and contributes to an overall high quality of life. The template code provides for a variety of open space types, which should be planned within the appropriate walking distances from all uses.

Universal Design

Universal design refers to principles that produce buildings and public spaces that are accessible to people of all ages and abilities, emphasizing equity and flexibility in use, especially the elderly and users with special needs. Universal design principles can be found in all sections of the template code.

Sustainable Infrastructure

A neighborhood’s infrastructure plays an important role in its overall sustainability. Opportunities exist in features like streets, sidewalks, lighting, sewers, and stormwater collection to improve sustainability throughout a neighborhood through strategies such as recycled material and water efficiency. The template code will provide for these kinds of occurrences.

Districts permit a mix of uses and building types. Some districts permit a fairly succinct set of uses permitted within only a couple of building types, while other districts are very flexible, permitting a wide range of uses in a variety of different allowed building types.

The assembled Wasatch Choice Visual Library, accessed via the link in the “Helpful Links and Downloads” section, is an image gallery of best practices and development concepts of the Wasatch Choice. Images are categorized into place types, street types, building types, open space, landscaping, parking, and signs. The images are designed to be context sensitive to the Wasatch Front and demonstrate what is possible through good design.

The image library is intentionally broad to appeal to different community needs and projects. Where most professionals have the need for quality images, they do not always have access to them. This resource aims to meet the image needs of many users and may be utilized for a variety of planning purposes, such as visual preference surveys, illustrating examples of good design in planning documents, form-based ordinance work, presentations, and more.

The visual library is intended to be a collaborative and on-going process that will update as new examples and designs emerge in this ever-changing field. Feel free to use and source any images from this library as long as they are used not for profit purposes. Images should be credited to the Wasatch Choice Visual Library, unless directed to give more specific credit in the comments of the individual image. If you wish to submit an image, please send email it to Megan Townsend.

Form-Based Code

While zoning code and long-range plans must address the broad goals of their community, it is important to be aware of and to communicate their localized effect through visual examples. In using the visual library, it is important to consider not only what is desired for your community now, but what the design of future growth will look like. While attempting to recreate exactly what is shown in these images is often neither feasible nor desirable, having an idea of what can be achieved is helpful in any stage of the planning process. These images are particularly useful to provide examples of zoning codes that have an emphasis on form and design. Dense code language can often lose sight of the realities it will produce on the ground and descriptive images are useful in explaining design concepts. The categories into which the images are sorted directly correlate with chapters in the Wasatch Choice Form-Based Code Template and Manual.

Are form-based codes really new?

No, hundreds of communities have used all or part of a typical form-based code in their zoning. Form-based codes are an emerging trend since they help foster economic development by reducing processing time.

What is the difference between traditional zoning and form-based codes?

Form-based codes encourage place making while traditional codes simply attempt to reduce impacts between uses. Form-based codes address more aspects of place making, such as street configurations, walkability, how buildings should encompass the street, street furniture, people-oriented signs, etc. than traditional codes. Zones created under a form-based code are particular to the place and not generic. Form-based codes implement the vision for the area.

Isn’t the Utah Form-Based Code Template/Manual really just a code I can use right off of the shelf?

No. The Utah Form-Based Code Template/Manual is intended to be a process where communities can engage in planning a place with a very specific ordinance to implement that plan.

Doesn’t a form-based code ignore land uses?

No. There is a chapter to define appropriate land uses that becomes an important discussion as part of the process of site specific calibration.

Why is it important to do a detailed visioning process first?

Form-based codes implement the vision. The clearer and more directed a vision is toward each of the components of a form-based code, the easier it will be to implement that vision with a form-based code.

Why do form-based codes promote more permitted uses?

The philosophy that a form-based code implements a vision, includes the idea that permitted uses should move development toward the vision. As developers help implement the vision through their construction, if their proposal is in harmony with that vision, communities should make it easy for them to move to the building stage as quickly as possible.

Why does a form-based code address streets and blocks?

Block length and street cross sections are some of the most important components of walkability for an area. Mixed-use places include a vibrant street environment, which promotes the concept of people using the public realm while walking, exercising, working, shopping, and lingering for social activities.

Why should I use Adobe InDesign to create a form-based code?

The template/manual was created in InDesign to facilitate the calibration of the template to the local site. InDesign allows for modifications of the graphics to occur with the least effort. New diagrams, charts, pictures, and sketches can be created and then easily brought into the code as objects for placement on a page.

What version of InDesign do I need?

It runs in Version 5 and any of the more recent updates.

Does a form-based code address density (i.e. – units per acre of FAR)?

Not directly. Density should be addressed in the visioning effort and then the form-based code implements those guidelines through standards that address height and coverage. Some typical densities are suggested in the workbook for different types of centers.

What communities in Utah are using form-based codes?

North Temple and 400 South Hybrids–Salt Lake City; Sugarhouse is in the adoption process; West Valley Hybrid; Eagle Mountain, Saratoga Springs and Springville are in development stage; Provo Hybrid; Heber City Hybrid; Park City; Farmington; Sandy Hybrid; Ogden Hybrid; North Logan; Magna, South Salt Lake, Salt Lake County/Meadowbrook are using the Utah Form-Based Code Manual/Template.