StreetPlan is a web-based platform designed to foster informed dialogue between the public and community leaders. Its extensive graphics, speed, and ease of use allow a group to collectively visualize, compare, and modify street alternatives. Its interactive elements inform users of regional plans, right-of-way constraints, basic engineering standards, and nationally recognized best practices to influence more informed decisions. Street designs can be quickly saved, printed, and downloaded, and incorporated into design programs.

StreetPlan is a web-based platform designed to foster informed dialogue between the public and community leaders. Its extensive graphics, speed, and ease of use allow a group to collectively visualize, compare, and modify street alternatives. Its interactive elements inform users of regional plans, right-of-way constraints, basic engineering standards, and nationally recognized best practices to influence more informed decisions. Street designs can be quickly saved, printed, and downloaded, and incorporated into design programs.

StreetPlan surmounts barriers inherent to street design communications. It allows users to design a street interactively rather than with static graphics, which helps build consensus. The review is ‘live’ and publication is at the users’ fingertips. Additionally, over time, StreetPlan will continue to enhance the design discussion by incorporate engineering principles and best practices into the discussion.

A picture is worth a thousand words. StreetPlan’s simple graphic interface allows users to quickly design and visualize street alternatives. It promotes a collaborative dialogue within the community, empowering local elected officials with the input they need to make informed decisions.

The tool is free, easy to use, and available to everyone to access either through StreetPlan.net. Internet access is required to use this tool.

For additional information regarding the tool, please contact Ted Knowlton.

How does Utah define Complete Streets and what are the benefits?

Why Complete Streets?

Streets are a valuable public asset to be shared by everyone regardless of their method of travel. About seventy-five percent of the costs of streets in Utah are paid for by everyone through general funds rather than gas taxes. Learn more via the Tax Foundation article.

One of the goals of Complete Streets is that streets should be safe for all permitted users and convenient for likely users when possible.

Streets are also a huge public asset, as they comprise about 30 percent of our urban spaces and the vast majority of our public spaces. Streets can bring us together but they can also become community barriers.

What Are Complete Streets?

Complete Streets are policies, plans and procedures adopted by local jurisdictions and transportation agencies. They are fashioned by the very local jurisdictions and agencies that will be guided by them.

Policies and procedures that ensure that all users are considered each time a street investment is made. All users include transit patrons, cyclists, and pedestrians of all abilities as well as freight.

These policies joined with robust, multi-modal network planning allow each community to uniformly weights the trade-offs of accommodating or not accommodating each type of user.

Complete Streets policies are not a mandate to construct accommodations for all users but only to methodically consider accommodations for all users. Because each street is tailored to its circumstances, Complete Streets take a great many forms.

There are many guides to developing a functional policy. Although each community is unique, there are national and regional resources that can help guide the development of a community strategy, policy, and implementation.

A. Individually Facilitated Complete Streets Strategy, Policy, and Implementation Procedure Workshop Program (Pilot)

Pilot program to provide personalized help in crafting a strategy, policy, and implementation procedures for Complete Streets. The minimum requirements for these cities are to have participation from at least one elected official, city manager, lead planner, and lead engineer.

B. National Complete Streets Coalition Local Policy Workbook

The workbook may be downloaded from the “Helpful Links and Downloads” section.

C. Ten elements of a comprehensive Complete Streets Policy

- Sets a Vision: A strong vision can inspire a community to follow through on its Complete Streets policy. Just as no two policies are alike, visions are not one-size-fits-all either. For example, Wasatch Front Regional Council’s (WFRC) Vision Statement reads: Complete Streets improves the value of the Wasatch Front region’s transportation network through a variety of connected transportation choices designed to meet the needs of all users. In the small town of Decatur, GA, the Community Transportation Plan defines their vision as promoting health through physical activity and active transportation. In the City of Chicago, the Department of Transportation focuses on creating streets safe for travel by even the most vulnerable – children, older adults, and those with disabilities.

- Specifies All Users: A true Complete Streets policy must apply to everyone using the public right-of-way regardless of age, ability, or mode of transportation. Users to be considered include but are not limited to adjacent businesses, residents, and visitors; freight, autos, and transit users; and pedestrians and cyclists of all ages and abilities.

- All Projects: Complete Streets policies apply to new construction, reconstruction, rehabilitation, repair, and maintenance. They build upon each transportation improvement to create safer, more accessible streets for all users saving time and money in the process. Examples include the following.

- Transit: Providing space in traffic signal control boxes for transit signal priority when such is anticipated.

- Cycling: Shifting the edge stripe to give cyclists more room.

- Elderly: Increasing the allocated pedestrian walk time at traffic signals when demand is present.

- Exceptions: Complete Streets policies and procedures spell out under what circumstances specific user types will not be accommodated and provide a clear process for granting these exceptions. In addition to defining exceptions, there must be a clear process for granting them, where a senior-level department head must approve them. Any exceptions should be kept on record and publicly-available. Common exceptions include the following.

- Accommodation is not necessary on corridors where non-motorized use is prohibited, such as interstate freeways;

- Cost of accommodation is excessively disproportionate to the need or probable use; and

- Documented absence of current or future need. Many communities have included their own exceptions, such as severe topological constraints.

- Creates a Complete System: Complete Streets policies paired with robust intermodal network planning result in a complete transportation system. Instead of trying to make each street perfect for every traveler, communities can create an interwoven array of streets that emphasize different modes and provide quality accessibility for everyone.

- All Agencies and Roads: Creating Complete Streets networks requires collaboration among many different transportation agencies. Street networks are frequently built, operated, and/or maintained by variety of entities including the state, county and local governments, and private enterprise. The Policies developed by Trenton, NJ and Bozeman, MT provide solid approaches to this policy element. The Utah Department of Transportation has adopted an Active Transportation Policy which will further facilitate the consideration of all users’ needs on Utah State Roads.

TRENTON, NJ: “Recognizing the inter-connected multi-modal network of street grid, the City of Trenton will work with Mercer County, the Delaware River Joint Toll Bridge Commission, traffic consultant AECOM, and state agencies through existing planning efforts to ensure complete streets principles are incorporated in a context sensitive manner.”

BOZEMAN, MT: “The City of Bozeman will work with other jurisdictions and transportation agencies within its planning area to incorporate a Complete Streets philosophy and encourage the Montana Department of Transportation, Gallatin County, and other municipalities to adopt similar policies…Complete Streets principles will be applied on new City projects, privately funded development, and incrementally through a series of smaller improvements and activities over time.” - Design Criteria: Communities adopting a Complete Streets policy should review their design policies to ensure their ability to accommodate all modes of travel.

- Context-Sensitive: An effective Complete Streets policy must be sensitive to the community context. The recommended practice by the Institute of Traffic Engineers in Context Sensitive Solutions in Designing Major Urban Thoroughfares for Walkable Communities uses “context zone” (urban form), street functional class, thoroughfare type, and typical land use to guide context related design decisions. Others may add street design vehicle. This policy element can allay fears that the policy will require every mode on every road resulting in little-use facilities and inappropriately wide roads. It also helps align transportation and land use planning goals, creating livable and strong neighborhoods.

- Performance Measures: Pearson’s Law says “that which is measured improves.” Complete Streets moves beyond the traditional, auto-centric measure of congestion. Complete Streets planning requires taking a broader look at how the system is serving all users. Communities with Complete Streets policies can measure success through a number of ways ranging from the simple to the complete.

MMLOS and LOS OPTIONS

Highway Capacity Manual 2010 (Transportation Research Board)

Pedestrian and Bicycle Level of Service (Charlotte, NC)

Automobile Trips Generated (San Francisco County Transportation Authority)

San Jose Transportation Impact Policy (City of San Jose, CA) - Implementation: The first step in implementation is an assessment of the existing street design process, procedures, and standards. Some policies establish a task force or commission to work toward policy implementation.

Assessment Sample – San Francisco, CA

Complete Streets take many forms. Each Complete Street is unique and responds to its community context. A Complete Street in a rural area may look very different from its urban or suburban counterparts. Nonetheless, each are designed and operated to be safe for all permitted users and convenient for all future likely users.

Designing complete streets is much more than a pen and paper exercise. There are five basic elements to good complete street design these are as follows:

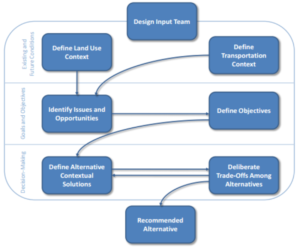

- Assembling the Design Team: Assembling the design team is, in some respects, an iterative process with ‘Defining the Context.’ In small, rural jurisdictions the team may be simply the planner and engineer. In larger, urban and suburban areas the core membership may be much larger. The core of a large team could include a project manager and a Complete Streets point person, as well as representation from engineering, planning, public works (maintenance), and public safety. This larger team might also be comprised of occasional representation from modal organizations representing likely users such as public transit, cyclists, freight haulers, businesses, and people with disabilities.

- Defining the Context: Defining the Context includes both the land use context and the transportation context—both current and future. The guidance provided by the Institute of Transportation Engineers (ITE) Context Sensitive Solutions in Designing Major Urban Thoroughfares for Walkable Communities links “context zones”, predominant land use, functional type, and thoroughfare type and provides design guidance based upon the intermixing of these contexts. Local and regional plans can provide the practitioner with guidance with regard to the future land use and transportation context.

- Identifying the Goals and Objectives: Developing goals and objectives can be done through several approaches and some or all can be implemented. Approaches include the following.

- Consulting local and regional plans.

- A review of Complete Streets benefits may also be helpful.

- Using a checklist to guide your thought processes.

- Assessing the Design Standards and Trade-offs: Standards are prevalent throughout the street design community. However, often what is overlooked are the variety of standards available and the flexibility inherent in the standards. The following tools stand out in respect to ease of use and information available.

- Both PEDSAFE and BIKESAFE have a countermeasure selection tools which allow the practitioner to input data on specific roadways and goals for the desired change in the facility. The tool then outputs different countermeasures, including engineering designs, which can be implemented in order to achieve the desired goal. The sites each house a crash type matrix, performance objective matrix, and case studies, including cost ranges for implementing countermeasures and actual costs for case study projects.

- StreetPlan is a web-based, interactive street design dialogue tool to surmount barriers inherent to street design communications. It is to be built in three phases. he first phase is primarily a simple cross-section builder. It is simple, free, and relatively easy for anyone to use. A common use of StreetPlan 1.0 is to facilitate a group in exploring street cross-section design alternatives in the context of the available rights-of-way through a three-step process:

- Prior to the meeting the facilitator “builds” the current street cross-section entering the correct right-of-way and curb-to-curb widths and copies and renames the current cross-section as alternative 1, alternative 2, etc.

- At the meeting the facilitator leads the discussion of the future street context, modal priorities, and the street functional class and thoroughfare types using, among other things, the dialog box accessed by clicking on the blue street title.

- Finally, the facilitator projects StreetPlan in ‘comparison-view’ onto a large screen and modifies each of the alternatives as guided by the group. Multiple alternatives can be made and compared to each other and the ‘current’ cross-section in this way. The selected alternative can be renamed as ‘consensus,’ saved, printed, and published to the web at will.

- StreetPlan 1.0 dispenses with the need to build a design consensus with static graphics or guidance. If the target street widths are exceeded, StreetPlan tells you. No need to let the consensus ‘grow cold’ over time while graphics are prepared for review and publication. Review is ‘live’ and publication is at the users’ fingertips. Although the dialog box is currently simple and should be supplemented by other sources, it will be greatly upgraded in future StreetPlan versions. Additionally, the ability to ‘draw’ the cross-sections longitudinally in Google Earth will also be added in future versions.

The region’s transportation partners have embarked upon a continuing, cooperative, and comprehensive effort to incorporate Complete Streets into our regional plans, policies, funding streams and facilitate our partner governments and agencies in doing the same.

Regional Complete Streets Organization and Contact Information

Complete Streets is led on the technical level by a multi-agency Complete Streets Steering Committee and on a policy level by the Active Transportation Committee.

- Wasatch Front Regional Council

- Mountainland Association of Governments

- Utah Department of Transportation

- Utah Transit Authority

- Weber County

- Davis County

- Salt Lake County

Funding Sources

Learn more about the available funding sources by visiting the following website pages.